Feeding People for Social Change

Roxana Pardo Garcia and her partners founded Alimentando al Pueblo, a Latinx-specific food bank, to support the Latinx community and feed a cultural need.

Few things are as comforting as homecooked food, especially food you've known since you were a kid. The smell and taste of a dish you grew up with has the power to revive potent memories and connect you to generations of family, community and culture.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began sweeping around the globe, Roxana Pardo Garcia saw members of her own community starting to lose access to this cultural anchor — not just culturally relevant ingredients, but the overall organizational culture to honor their Latinx identity.

Pardo Garcia joined forces with other founding partners to create Alimentando al Pueblo, a Latinx-specific food bank serving the Highline area near Seattle, where Pardo Garcia was born and raised.

Pandemic Increases Need

"When the pandemic hit, a lot of us who understand racism and who are scholars predicted what was going to happen," said Pardo Garcia, who has a degree in American ethnic studies from the University of Washington. "I had this overwhelming sense of doom."

That sense of doom stemmed from the awareness of the systemic drivers that would lead to disproportionate and heavy losses communities of color would face during the pandemic. COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and death rates were higher among minority racial and ethnic groups than whites nationally, according to a study published by the National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine.

From an economic perspective, Latinx people, who are overrepresented in the service industry, accounted for 23% of the initial job losses during the pandemic, according to American Progress.

A Healing Solution

Pardo Garcia wanted a way to help address the practical fallout of not being able to get food on the table while also addressing the emotional and psychological damage of enduring pain.

"I was thinking about all the babies who were going to be born during the pandemic to people experiencing trauma, hurt, grief and loss," Pardo Garcia said. "We needed to help people start to write memories that are associated with joy and community."

At the time, she was doing community work for a government agency, but the agency couldn't respond quickly enough to bring immediate relief.

"I knew my network already had what it takes to take care of each other, so we decided to go ahead and do it," she said.

She reached out to her "homegirls," executive directors at nonprofits, and asked them what they thought of the idea: "None of them hesitated. They asked, 'What do you need?'"

Her nonprofit connections responded with volunteers and grants to support the effort. Pardo Garcia, her mother and three other women launched Alimentando al Pueblo.

Why Culturally Relevant Food Is a Priority

Through Pardo Garcia's career in community advocacy work, and her own friends and family, she has seen how food banks can miss the mark by assuming everyone needs the same kind of help.

"My aunt said she wouldn't go to a food bank because they don't have food she can cook with," Pardo Garcia said.

She explained that providing food without considering culture and identity can be dehumanizing to people who are already experiencing the stress of needing and accepting help.

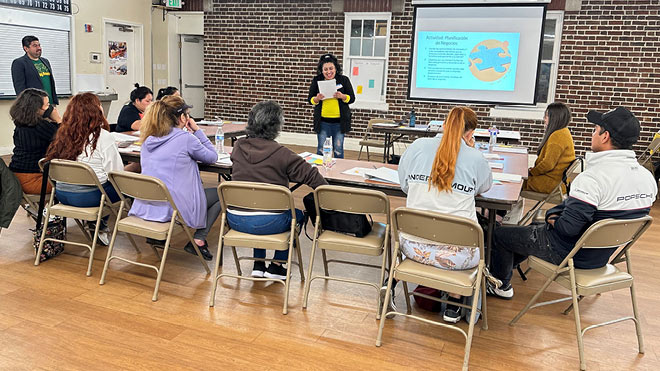

A Warm and Generous Place

In addition to not being able to find food you identify with, Pardo Garcia said the atmosphere where people go for help can feel unwelcoming and often emphasizes scarcity, with industrial grade furnishings and little décor.

"People told me they wouldn't go to a food bank because they didn't feel comfortable," Pardo Garcia said. "We're activating a base of people who have not historically been served."

It's important to Pardo Garcia and her team to cultivate a celebratory environment that feeds all the senses with familiar cultural touchpoints. People receive needed food and supplies that Alimentando al Pueblo purchases from local businesses while local artists display paintings and play music.

"Our entire model is based on our commitment to a culture of abundance," Pardo Garcia said. "We're reversing the lie that there isn't enough for everybody."

Meeting the Demand

The numbers suggest a longstanding need is finally being met: In 2020 and 2021 (the latest numbers available), Alimentando al Pueblo has served 1,170 families, 4,680 individual community members, and 300,000 pounds of food.

Despite the community rallying to answer the call for support, getting enough funding to continue addressing the need has been challenging.

Pardo Garcia raised the initial funding through a GoFundMe campaign that surpassed her $10,000 goal by $20,000. Nonprofit partners contributed grants, and a few months later, King County requested proposals for culturally relevant food options. Alimentando al Pueblo applied and won $270,000 in grants from the county.

Then the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 provided a much-needed infusion of funds, bringing total funding to half a million dollars.

Even though she's grateful for the grants, the funding comes with strings attached that make it difficult for Alimentando al Pueblo to staff its programs. Paying a living wage is a priority and fundamental part of the organization's values.

"The constraints about how much can go to staff and administration are brutal," Pardo Garcia said. "There's money to provide food, but we need to pay people to do the work."

Since its launch in 2020, Alimentando al Pueblo's paid staff has grown from five founding partners (including Pardo Garcia and her mom) to a staff of 16. They are supported by five unpaid volunteers.

'Trabajo Bien al Gusto'

Bringing Alimentando al Pueblo from concept to reality at the height of the pandemic has been no easy task, and daily operations are busy. Pardo Garcia described the hustle of processing a delivery of 100 boxes to get them ready before the doors open.

Yet, the team keeps their cool, embracing the idea of "trabajo bien al gusto," a Spanish phrase for working in comfort and not feeling rushed, Pardo Garcia said.

"We're trying to create an environment where people don't feel strained. We cannot afford to continue to traumatize our people. We don't bring our franticness and chaos to work. We bring a sense of calm."

Pardo Garcia and her team hope their efforts will help restore a sense of community, and even help people regain some of the creativity that is lost when they are concerned only with taking care of their basic needs.

"We honor their humanity, labor and well-being," Pardo Garcia said. "We provide a space to dream and think about what's possible."

Resources

The above article is intended to provide generalized financial information designed to educate a broad segment of the public; it does not give personalized financial, tax, investment, legal, or other business and professional advice. Before taking any action, you should always seek the assistance of a professional who knows your particular situation when making financial, legal, tax, investment, or any other business and professional decisions that affect you and/or your business.