Barriers to Indigenous Wealth

Learn about some of the barriers that have prevented many Native Americans and Indigenous people from thriving financially in the United States.

High income and wealth are difficult to achieve in the U.S. for many Native Americans. To find opportunities to advance racial equity for Native Americans, it's important to understand how big the income and wealth gaps are and learn about the history that led to those gaps.

What Data Says About Native American Income and Wealth

Consider these statistics:

- The median household income for Native Americans is $43,825 compared with $68,785 for white, non-Hispanic households — about 64% of white, non-Hispanic median household income.

- The average Native American household has 8 cents of wealth for every dollar of wealth for the average white American household.

- Native Americans have the highest national poverty rate at 25.4% compared with 8% for white Americans, according to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition..

- The homeownership rate was 51% among Native Americans, compared with 73% for white non-Hispanic Americans in 2019.

Even though the statistics describe financial health on average, Native Americans are not a monolithic group. There are hundreds of tribes, nations and bands, each with unique languages and cultures. We can look at the numbers in aggregate because of the shared history of trauma, oppression, displacement and cultural erasure in the U.S. that continues to block Native American financial growth and stability.

Here are some of the factors that have inhibited many Native Americans' access to building financial wealth and passing it on to future generations.

Colonization

Systematic colonization began more than 500 years ago, with the arrival of European settlers who claimed land for themselves that had already been occupied by Indigenous people for centuries.

The settlers violently forced their way onto the land, displacing Indigenous people. The English claimed all the land east of the Mississippi after winning the French and Indian War of 1754-1763. Colonizers enslaved Native Americans who were allies of the losing side.

Colonizers also brought with them diseases for which Indigenous people had no immunity. By some estimates, illness killed as much as 90% of Native American populations.

That loss of life and land has been putting Native Americans at a severe financial disadvantage ever since colonizers arrived.

Forced Relocation and Genocide

As the United States government formed, the takeover of Native American lands continued. The settlers drew borders and developed land for individual economic gain, building financial wealth they could pass down to future generations of their own families.

Contrary to popular belief, Native Americans understood land ownership and owned land themselves, although there were, and in many ways still are, significant cultural differences between the Native American and settlers' approach, and among tribes in how land and resources were managed, how value was assigned, and whether the benefit was communal or for individuals.

Many white settlers believed they were entitled to the land, and the presence of Native Americans interfered with their plans. So, the settlers took the land, often violently, burning down houses and even committing mass murder. President Andrew Jackson referred to this as the "Indian Problem." To make room for the settlers, and their lucrative industries such as cotton farming, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830 giving the federal government the authority to take Native American land in the east in exchange for land west of the Mississippi.

Native Americans from different tribes were marched thousands of miles, many in chains with little or no food, to what the federal government had designated "Indian Territory." About 3,000 Native Americans died of starvation and disease along what would become known as the Trail of Tears.

When colonization began, the North American Indigenous population was estimated at 5 million to 15 million. By 1900, about 400 years later, the population dropped to fewer than 238,000.

Reservations and Forced Assimilation

In 1851, the Indian Appropriations Act created the reservation system. Tribes were moved to land they were told they could farm, but it was often on unwanted land, where nothing could grow. Native communities struggled to maintain their culture. Tribes were forced to wear non-Native clothes, cut their hair, abandon their language and give up their spiritual beliefs.

The Dawes Act of 1887 further reduced the amount of land in Native American control. The law divided the tribes' land into tracts that would be allotted to individual Native Americans. Once the allotments were made to tribal members, the remaining land was sold to white Americans. As a result, Native Americans lost an estimated 86 million acres, or 62%, of their land.

Trust Land and Limited Property Rights

Native American reservations are sovereign nations that aren't subject to federal laws, but the federal government holds much of the tribal lands in trust, hampering the wealth-building potential of the land for the tribe and its members. In many cases, Native Americans can't build equity and pass it on to their children. They can't take loans against their property, sell it or develop it in the same way private property owners who hold the property title can.

There is debate about whether individual ownership or communal ownership would most benefit a tribe, but the existing system doesn't give tribes the choice, leaving many out of a common method of building wealth.

Lack of Access to Banking and Affordable Credit

An estimated 16.3% of Native American households are unbanked, meaning they don't use banks or credit unions, representing the lowest rate of banked households in the country, according to the National Indian Council on Aging.

Often, people are unbanked because of poor credit history or distrust of the banking system. Without a traditional bank, they must rely on non-traditional financial service providers to cash paychecks, take out money orders to pay bills, and borrow against upcoming paychecks. These services typically come with high fees and interest rates.

Native Americans who live on reservations often have the additional challenge of traveling long distances to financial institutions and ATMs, and spotty internet access that makes online banking difficult.

So how far is it? On average, it's 12.2 miles from the center of a Native American reservation to the nearest bank or credit union.

To fill the void left by traditional banks, Native Americans have built banks and credit unions to meet the needs of the communities they serve. According to the National Indian Council on Aging, there are 30 Native American and Alaska Native banks and credit unions in the U.S. working to provide financial assistance and banking services to communities and tribal-owned businesses.

Long-Lasting Effects

The history of violence and stolen land set the starting line for building financial health and wealth farther away for many Native Americans. Colonizers and the federal government created mechanisms to give white Americans a head start in a world that was new to them and forcibly removed Indigenous people. By controlling the borders and holding land in trust, the federal government has retained control of Native American populations, despite their sovereign status.

How To Support Native and Indigenous Financial Health

First, understand the meaning of Indigenous wealth. According to the Native Governance Center, it's about decolonizing and revitalizing what it means to be healthy and live in abundance.

Consider these three ways to support Indigenous wealth:

1. Self-assess.

If you're interested in supporting Indigenous wealth, a self-assessment is a great starting place. Look at what you're already doing. How are you contributing to or potentially harming the financial well-being of Indigenous people? Are you involved with efforts happening in your own community? The Native Governance Center put together a self-assessment as a reference for individuals and groups aiming towards working in solidarity with Native nations.

2. Take action.

Look for meaningful ways to listen and learn from Indigenous people. Can you advocate for or amplify Indigenous voices in your workplace? Your community?

- Sign up for a class. Look for classes that share information about tribal sovereignty, tribal history and governance. Local community colleges may offer classes on these topics.

- Vote. Voting is an important way to make your voice heard. Also try encouraging your friends and family to vote. You can make a difference on issues being voted on in local, state and tribal municipalities.

3. Consider donations.

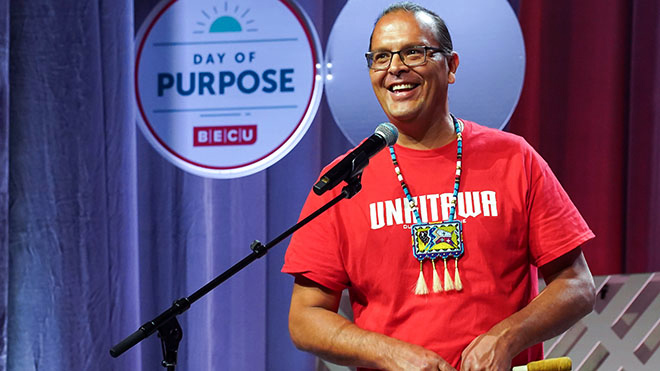

If you're able, consider making donations to Indigenous wealth-building organizations. You can join BECU's Native Indigenous Peoples Employee Resource Group in contributing to causes they are working to advance: Chief Seattle Club, Duwamish River, Rise Above, Unkitawa and Whale Scout.

The above article is intended to provide generalized financial information designed to educate a broad segment of the public; it does not give personalized financial, tax, investment, legal, or other business and professional advice. Before taking any action, you should always seek the assistance of a professional who knows your particular situation when making financial, legal, tax, investment, or any other business and professional decisions that affect you and/or your business.